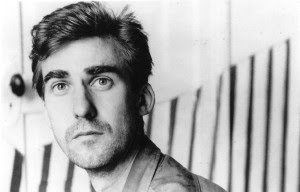

JESS was born in 1923 in Long Beach, California, the younger son of a civil engineer and a homemaker. Originally named Burgess Franklin Collins, he later broke with his family and changed his name to “Jess.” In childhood, Jess read the L. Frank Baum Oz books, Poe and Proust, listened to the music of Beethoven, Mahler, Sibelius and Brahms, and made scrapbooks with a great-aunt, which he credited as one origin of his later collage work.

In 1942 Jess began studying chemistry at the California Institute of Technology but was drafted into the Army Corps of Engineers in 1943. In a very junior role, he worked until 1946 at the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, on the production of plutonium for the atomic bomb. Following the war, he completed his degree at Cal Tech with honors in radiochemistry and went to work at the Hanford Atomic Energy Project in Washington.

During his time at Hanford, Jess began to study painting in adult education classes, while at the same time growing concerned about the nature of his participation in atomic energy work: “I was involved with nuclear energy, the direction it was going seemed questionable, nightmarish in many ways.” In 1948 he was visited by a terrifying dream that foretold the destruction of the world in 1975. Within months, he had left his job, decided to pursue art full-time, moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, and found his way first to the University of California at Berkeley and soon to the California School of Fine Arts, now the San Francisco Art Institute.

At CSFA, he studied with Elmer Bischoff, Edward Corbett, David Park, Hassel Smith and Clyfford Still. Taking inspiration from Clifford Still’s aesthetic breadth and tolerance, Jess explored both abstraction and figuration, learning from Still “a poetics of materials.” As he said later to Michael Auping, “I personally didn’t see any reason to make a dichotomy between abstraction and representation……It was all paint.” His interest lay in the redemptive powers of imagination and myth, which he regarded as one with the materials: “I don’t see that much difference between the spiritual and the material. All matter is energy, and all matter and energy are infused with spirit.”

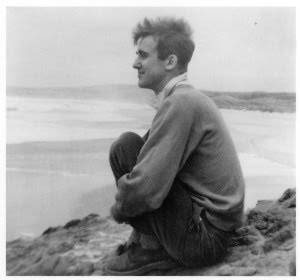

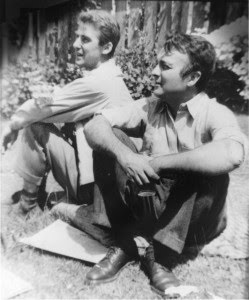

Jess & Robert Duncan c. 1958-59 at Stinson Beach, CA

When Jess met poet Robert Duncan in 1950, they soon discovered their shared love of Baum’s Oz books and James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, and the future of their lifelong romantic relationship, domestic household, and artistic collaboration was established. The 2013-14 exhibition and catalogue, An Opening of the Field: Jess, Robert Duncan and their Circle, documented the brilliant artistic fecundity of their bond and its importance to San Francisco artistic and literary communities. Their idea of the “household,” a place of domestic love but also of spirited, generative collaboration, became central to the development of their art and poetry.

Throughout the fifties, Jess experimented with technique in still lifes, portraits, and landscapes, paintings that shimmer with narrative potential. Jess described some of these works as “mythic landscapes, in the sense that a certain abstract chaos is slowly coming to order. All of the creation myths depict some kind of chaos transforming into order or image. I sometimes thought of these early landscapes as vaguely analogous to a creation myth.”

Inspired in part by a gift from Duncan of Max Ernst’s surrealist collage book Une semaine de bonté (1934), Jess also began making collages, or in his term, “paste-ups,” in the early fifties, combining text and image fragments of engravings, photographs, comic strips, and jigsaw puzzle pieces. These works, becoming ever more complex over time until they were comprised of hundreds or even thousands of distinct elements, led critic Jed Perl to compare Jess and Joseph Cornell as “….American originals, highly sophisticated artists who weren’t afraid to be seen as outliers or cranks.”

The thirty-two works in Jess’s important Translation series, begun in 1959, are painted, enlarged reproductions of found images including photographs, children’s book illustrations, post cards, pages from old Scientific American magazines, Krazy Kat cartoons, and illustrations of art, science and math subjects. Every image is combined, either within the painted surface or on the backs of the canvases, with literary texts from a wide variety of sources including Wordsworth, Blake, Gertrude Stein, Plato, Aztec and Mayan poems, scientific texts, Kandinsky, Gaelic songs and Edward Lear.

Thickly painted, the surfaces are highly textured, sometimes rough, and occasionally billowing. Describing the colors, Jess explained, “I want to get the level of light that was in the original. My colors are absolutely imaginary, not realistic. At my best, I want to pay homage to the original and a completely imaginary complex of color that is my translation of that original.” Of the Translations, Michael Auping has said, “The mysterious irony of the ‘Translations’ is that they are highly reverent copies that are, in themselves, entirely original, which of course brings into question whether or not they are copies at all. The ‘Translations’ are not secondary to the ‘originals’ but are, in Jess’s words, ‘spiritually coexistent’ with them.”

For his later Salvages series, instead of copying, or “translating” a painting onto a canvas from a found object, Jess painted, or repainted, directly over his own earlier discarded canvases or paintings found in thrift shops. Leaving the thinner surface of the original painting bare in places, he built up a thicker layer of paint around fragments of the original images, adding texture and new images, encouraging unexpected meaning to develop. Like the Paste-Ups and Translations, the Salvages derive from images and texts found and saved, and add new beauty and mystery as the found materials are reinterpreted, expanding allegorical dimension in the process.

Narkissos, Jess’s most ambitious project, was begun in 1959 as a pencil drawing for a painting to be based on the myth of Narcissus but gradually evolved into a large scale mixed media work. It combines a monumental graphite rendering of the figure of Narcissus with pasted-up fragments of Jess’s own hand-drawn images as well as found sources of the Narcissus myth and its many iterations in literature, art and popular culture. The magnificent “unfinished” work is now in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Although it has often been written that Jess was a recluse who rarely left the house, in fact, though he did avoid crowds and large social gatherings, he was a domestic flaneur, a householder walking the streets of San Francisco to buy groceries, visit the post office, drop in on friends, lunch in his favorite Mission District eateries, and most importantly, to scavenge his way through the multitude of thrift and used book stores liberally sprinkled throughout the city in search of the materials that formed the foundation of nearly all his artwork. As he told Michael Auping when asked about the title of his Salvages painting series, “I’m always out shopping….Really all my work – Paste-Ups, Assemblies, Translations – comes from salvaging. I salvage loved images that for some reason have been discarded and I come across them…….I put forward a new layer of sentiment that, combined with the old, may hopefully allow the image to have a new life or at least a half-life.”

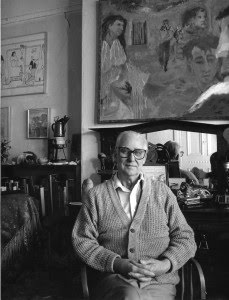

Aside from a period of travel with Duncan in the mid-fifties to Europe and Black Mountain College, Jess lived and worked in San Francisco for the remainder of his life. His large, Victorian home with Robert Duncan in the Mission District became a treasure house of art and literature, a household filled with artworks by Jess and their many friends, Robert Duncan’s vast library, their recorded music collection, and the many beautiful, rare and often slightly chipped or worn domestic objects salvaged from thrift shops with which they entertained their large but intimate circle of friends. In this home these two men, both passionately engaged with the world, created a world of imagination.

Jess’s first solo show was in 1950 at the Helvie Makela Gallery in San Francisco, soon followed by a show at the King Ubu Gallery, a small but important venue for alternative art founded in 1952 by Jess, Duncan and their close friend Harry Jacobus. Gradually Jess’s work became widely known through solo and group exhibitions in prestigious galleries and museums throughout the country. Works by Jess are now included in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Musuem, The Museum of Modern Art, the National Gallery of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Art, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and numerous other major museums. Attention to his work continues to grow, most recently as a result of the touring exhibit, “An Opening of the Field: Jess, Robert Duncan, and Their Circle.” Acknowledging the mark of a painter whose work was nourished by a community of affection, art critic Peter Frank wrote, “He sought approval of his friends – as well he should, given their own poetic standards – but not of the art world; even so, his art paralleled and even anticipated so much of his time’s art.”

Quotes, unless otherwise attributed:

Auping, Michael, “An Interview with Jess,” Jess: A Grand Collage 1951-1993, Albright-Knox Art Gallery,

Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, 1993, Buffalo, New York.

Auping, Michael, Jess: Paste-Ups (and Assemblies) 1951-1983,

The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art Foundation, 1983, Sarasota, Florida.

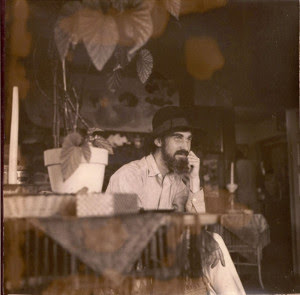

Assembly shelf in Jess’s studio

Photograph by Ben Blackwell